Taking down the walls: Challenges and opportunities of forgiveness

“If we could read the secret history of our enemies, we should find in each man’s life sorrow and suffering enough to disarm all hostility”

— (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)

“If we could read the secret history of our enemies, we should find in each man’s life sorrow and suffering enough to disarm all hostility”

— (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)

Medical literature contains numerous references proclaiming the benefits of meditation and mindfulness on cardiovascular health and pain management. But to me, these were merely academic case studies, as I had not personally known anyone who had successfully used mindfulness to manage through a major medical procedure. That is, until August 17, 2016, when I had aortic valve replacement surgery.

We have two lives, and the second begins when we realize we only have one.

It’s such a shame to think of how often we deride ourselves, and each other, for being “emotional.” It’s like jumping on someone for breathing. Emotion is a process that is a vital part of being alive. As the pioneering psychologist of emotions Paul Ekman has said, emotion is a kind of rapid, automatic appraisal of what’s going on. It’s influenced by our evolutionary past as well as our personal past, such that when “we sense that something important to our welfare is occurring…a set of physiological changes and emotional behaviors begins to deal with the situation.”

Using our personal strengths can enhance our mindfulness but mindfulness can also help us better use our strengths in life, work or sport. In the mPEAK program, participants become aware of how and when they are using their strengths and the results that they’re getting so that they can understand how to use them to the best effect.

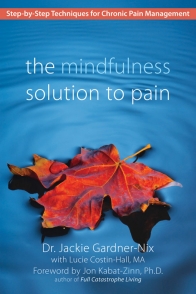

The Mindfulness-Based Chronic Pain Management (MBCPMTM) course is a modification of the Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction courses established by Jon Kabat-Zinn which are now world-wide.

The Mindfulness-Based Chronic Pain Management (MBCPMTM) course is a modification of the Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction courses established by Jon Kabat-Zinn which are now world-wide.

Researchers at UC San Diego School of Medicine who have been working with Olympic BMX cyclists to improve their athletic prowess have documented areas of the brain that appear to respond to mindfulness training.

Researchers at UC San Diego School of Medicine who have been working with Olympic BMX cyclists to improve their athletic prowess have documented areas of the brain that appear to respond to mindfulness training.

It’s a simple question, really. But one that often brings on a state of perplexed astonishment when someone asks us.

“What do you need?”

Unless we are a sobbing child who has come rushing to his mother after some sort of sibling transgression, or we are urgently and frantically searching for the restroom in an unfamiliar restaurant, we have an unusually hard time answering that question.

It’s summer time. A time for those of us who work on college campuses to take a deep breath and reflect for a moment on the school year just past, and make plans for the year a head.For me, this means thinking about our Koru Mindfulness program, looking at the number of students we served last year at Duke and contemplating how we can continue to expand our programming to meet the growing needs of students. Not surprisingly, this activity produces a surge of gratitude in me.

When asked what gets in the way of consistently performing at their best, most people can easily identify obstacles such as time, energy, scheduling conflicts, and distractions. These can indeed be areas that need focus but what I’ve found in my coaching practice is that most of our real obstacles are internal. Another way to say this is, our greatest obstacle to peak performance is often ourselves.

Scroll to Top